The world we wasted.

Social media corporations hold an evolutionary checkmate on us, and it's not necessarily your fault.

I wish I could delete social media

I wish.

Objectively speaking, very little prevents us from pulling the plug. Metaphysically? It’s a whole different story.

Dictated by a primal goal to survive, the burning desire for connectivity is sewn into the very seams of our existence. It’s quite simple really. The social caveman had more friends. More friends meant more popularity. More popularity meant more food, care, protection, opportunities to copulate, and thus, more chances to survive. Through trial and error, life and death, we’ve come to understand that social belonging is our best bet to see another day.

So much so that even today in a period of supposed perpetual peace - heavy emphasis on the supposed - we still often find ourselves in an endless bout of self-indulgent gaslighting. Desperately looking for the right combination of superfluous cop-outs that’ll preserve our pilgrimage to the little screen in our pockets. Like a karmic love we should have long let go of, we ruminate endlessly over any residual dopamine platforms may funnel our way.

A grainy video noire of American Psycho. Backing narration by a crypto bro telling you you’re wasted if you don’t have a Lamborghini by 30. A deep-fried acid green, some ironic text about ending it all, written in a font you already know. You laugh, ironically of course, but this is the 15th re-hash on your feed in the last hour.

When does irony cease to be ironic?

By nature of design, the platform realm teases us with the carrot of satisfaction on the end of a stick. Just out of reach, yet only ever a single swipe away. Deviating from the traditional website format we first inherited, platforms take this existential horror to a whole new level. On these vast new playgrounds, not only are we the horse, but also the carrot, the stick, and even the hand that dangles the treat for us to follow. All while tethered to a treadmill of sorts, living the illusion of moving forward. In some senses, we host algorithmic parasites. We don’t necessarily choose to nurture the illness, we’re simply nurturing our primal need for connection. Yet by sheer design, we’re not given much of a choice but to break bread with that which destroys us.

The platforms and algorithms? They’re far too busy for your concerns. They’re locked in, hustling, in ways that would have your favourite self-help podcaster up at night analyzing his reflection in the bathroom mirror. They’re learning, practising, and actualizing day in and day out. They dangle various objects before your eyes like a baby in a nursery and watch how you light up. Nodding and muttering amongst themselves, they frantically scribble down their observations, proving, disproving, and re-hypothesizing about what ruffles your feathers. See it how you will, the reality is that things are not as we inherited them. In a change so subtle, yet so monumental, we find ourselves being held at checkmate on the chessboard of life.

We are the consumers, right?

I think it would be a gross misrepresentation to assume so. As a matter of fact, I don’t even think we can classify ourselves as belonging to the internet era anymore. I couldn’t tell you the last time I had to type “www” in a web browser. Maybe to panic check Google to see if some random heart pain means I’m having a heart attack, or perhaps to learn how to poach an egg. We simply don’t exist on the internet as we remember it being handed to us.

Rather, we exist on platforms. Sprawling megacities of actors and marketers. Stylists and directors willing to sell a kidney to put a battered vintage jacket on some mid-tier celebrity. A digital Los Angeles of cheap alter egos fueled by an incessant need for attention and conversions. Any of us likely have a good enough shot at working for intelligence firms with the lengths we’re willing to go to control perceptive narrative. In this realm, we’re no longer the consumer, but the product itself. We’ve unknowingly handed the baton of purchasing power to the platforms, fueled by an algorithm stock exchange in which our attention spans are now the hottest currency on the market.

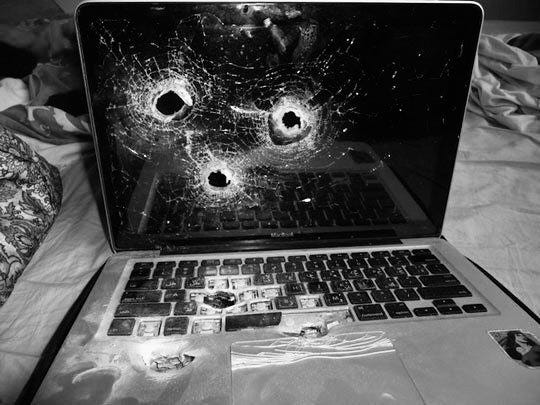

Platforms tear at us limb from limb like a school of sharks, gunning for every morsel of what little consciousness we have remaining, and more often than not, we’ll give it to them. Why that?

Because we’re humans. It’s foolproof.

Truly the greatest checkmate of all time.

It may have been our evolutionary wiring that made us susceptible to this consciousness heist, but we’ve paradoxically found ourselves to be more disconnected than ever before. On an evolutionary scale, the practice of reaching for a strange little screen at sixty-second intervals throughout an entire lifetime has become rendered a completely ordinary behaviour. Let that absurdity simmer for a moment. No virtue signalling, I’m just as bad as the next man, if not worse off. Throughout the process of writing my thoughts down for this piece, I must’ve reached for my phone every three sentences. This pitstop behaviour is a very new reality.

Most of us will still remember a time before we had the option to withdraw from our presence. What did you use to do when taking the bus? Waiting in line? Going to the bathroom? It just seems that what we broadly understand as mindfulness today used to just mean living an ordinary life. Adequately put by Hippocrates; “everything in excess is opposed to nature”, and the predicament we find ourselves in today can best be described as an excess of connection. An excess of individuality. An excess of ego. Beneath the incremental degrees of algorithmic authority indoctrinating us with the illusions of the self, there seems to be an underlying ominous teaching fueling the despair;

There is no higher virtue than the relentless pursuit of self-pleasure. Everyone and everything is a means to an end.

There is no we, only you.

Apathy and individualism have cemented themselves as the two iron gates to our capitalist utopia. Hand in hand, both brutal notions are adorned beautifully in the soft velvet drapes of self-care. With our noses high up in the air, we employ this pseudo-righteous alibi to liberate ourselves of that which we owe the world. Our time and effort. We feed our egos with ravenous gluttony, gorging on cheap thrills and even cheaper excuses. Gold medals in mental gymnastics. Each of us bounding away on our static treadmill, oblivious to the fact that we can just step off of it.

Apologies for the sermon. I’m done now. I just believe we can’t seek a solution if we don’t think there’s a problem to begin with. I’m sure in many ways it’s easier to just enjoy the view through rose-coloured vision pros as opposed to the unfiltered horrors of it all - and I can’t blame anyone for thinking so - yet there’s something inherently perverse about how unaccustomed we’ve become to existing with ourselves.

This is where the good news starts.

Sorry for the sermon, it’s over now. It’s no secret that I’m not alone in my sentiments; there seems to be something astir on the chessboard. A societal gambit of tectonic proportions is well underway, fuelled by a ferocious hunger to feel something again. Whether it’s those ten minutes you spend in the morning listening to some lady on YouTube cooing at you to breathe from your diaphragm, the journal you’ve retched your grief into, or the sleepless night you picked over a substance, all these decisions are motivated by the very same ambition.

To start living this life, instead of letting it live you.

I won’t lie though. Sometimes it does feel like it’s easier to ask everyone else to log out, just so I can be alone for a minute.

Then, I put the phone down...then , I picked it up to write this comment. Whoa!

Your piece captures the complexities of how social media manipulates our natural desire for connection, and I think a lot of people feel trapped in that cycle. The ‘checkmate’ metaphor is such a powerful way to frame it.

Personally, I don’t feel like I’m under that checkmate. I’ve intentionally distanced myself from a lot of social media platforms, and I rarely engage with things like algorithms or endless scrolling. That detachment has helped me avoid some of the pitfalls you describe, though I still see their effects on society around me.

It’s interesting to think about how not everyone’s relationship with social media is the same. Some people feel deeply entangled, while others manage to step back or avoid it altogether. What do you think it takes for someone to opt out? Is it more about personal choice, or does it require structural change to break free?

I appreciate how your piece invites reflection, even for those of us who aren’t deeply tied to social media. It makes me wonder: can those of us who’ve opted out in some ways still help shift the broader cultural narrative? Or are we just spectators in the game?